Surveillance plays a crucial role in monitoring and evaluating the trends of emerging diseases. It is crucial for better prevention and management of infectious diseases. Surveillance also helps in making evidence-based decisions. India had surveillance of certain drug-resistant organisms as part of national programs like Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP) and National AIDS Control Program (NACP). But a program dealing with multiple drug-resistant microbes was missing. The National Policy on AMR Containment in India prioritized the surveillance of AMR and antibiotic use across human and animal sectors. The policy advocated for the sentinel surveillance of AMR through facility-based testing. This led to the development of the National Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (NARS-NET)India launched the National Program on AMR Containment during the 12th five-year plan period (2012-2017). The program was coordinated by the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC). The main objectives of this program are:

- Establish a laboratory-based AMR surveillance system in the country to generate quality data on antimicrobial resistance

- Carry out surveillance of antimicrobial usage in different health care settings

- Strengthen infection control practices and promote rational use of antimicrobials through Antimicrobial stewardship activities

- Generate awareness amongst health care providers and the community on antimicrobial resistance and rational use of antimicrobials.

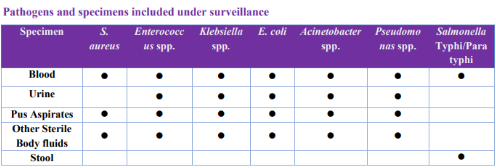

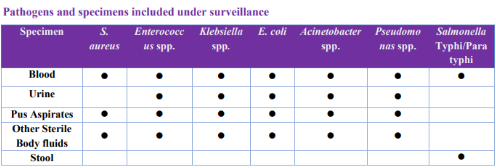

The NARS-Net India was established to fulfill the first objective of the National Program on AMR containment. Currently, 29 state medical college laboratories from 24 Indian states are part of this network. The AMR surveillance under this network presently includes seven priority bacterial pathogens isolated from 5 clinical samples.

The data is submitted by the network labs to NCDC using the WHONET software (computerized microbiology laboratory data management and analysis program) quarterly and feedback is provided to the labs by NCDC regarding the completeness of data. The corrected data once received is analyzed at NCDC and compiled in the form of an annual report.

The annual report for the year 2020 is available here. The quality of data submitted under the National AMR surveillance network is ensured through an External Quality Assessment Scheme (EQAS) conducted by NCDC, under which all network sites submit isolates every quarter (as per program guidelines) to the National Reference Laboratory established at NCDC. NCDC has also developed various SOPs, which are updated regularly, and all the sentinel site laboratories are provided training on the use of these SOPs. During onsite visits, the lab capacity is assessed and hand holding is done for strengthening Internal Quality Control and Proficiency testing in these labs. In addition, training is also provided on AMR data management using the WHONET software. Capacity building on standardization of basic procedures in Bacteriology across the network has also been initiated using the virtual platform in collaboration with CDC, ASM and ECHO-India. The AMR surveillance network sites are also mandated to submit AMR alert strains for confirmation to NRL at NCDC. NRL at NCDC also conducts molecular characterization of the AMR strains. Annual meetings are conducted to review the working of the network labs under the program.

Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance & Research Network (AMRSN)

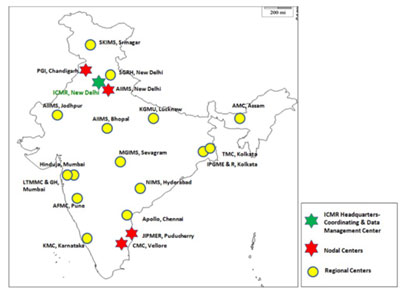

In 2013, ICMR initiated Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance and Research Network (AMRSN) to generate evidence on the extent of drug resistance and nationally representative data on AMR.

The main goals of ICMR AMRSN are to:

- Establish a network of hospitals to monitor trends in the antimicrobial susceptibility profile of clinically important bacteria and fungi limited to human health

- Include comprehensive molecular studies for identifying the clonality of drug-resistant pathogens and their transmission dynamics to enable a better understanding of AMR in the Indian context and develop suitable interventions

- Disseminate information on AMR in pathogenic organisms to stakeholders to promote interventions that reduce AMR

- Create a data management system for data collection and analysis

CMR's network focuses on six pathogenic groups: Enterobacteriaceae causing sepsis, Gram-negative non-fermenters, Enteric fever pathogens,

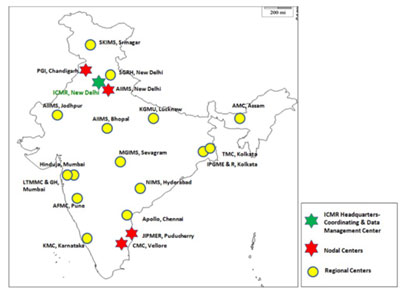

Diarrheagenic bacterial organisms, Gram positives (Staphylococci and Enterococci), Fungal pathogens-yeast (Candida and Criptococcus spp.) Iand mycelian fungi (Aspergillus spp. and Zygomycetes spp.) Hence, AMRSN includes six Nodal Centers (NCs) for each pathogenic group that is located in four tertiary care medical institutions. The surveillance network is managed by the coordinating centre at ICMR Headquarters in New Delhi along with the nodal centres. The six nodal centres are:

- Enterobacteriaceae causing sepsis: PGIMER, Chandigarh

- Gram negative non fermenters: CMC, Vellore

- Enteric fever pathogens, AIIMS, New Delhi

- Diarrheagenic bacterial organisms, CMC, Vellore

- Gram positives including MRSA: JIPMER, Pondicherry

- Fungal infections: PGIMER, Chandigarh

There are 16 regional centres (RC) in the network which are sixteen regional labs from tertiary care hospitals to provide data on a fixed number of isolates for each pathogenic group across the country. These are:

- Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences (MGIMS), Wardha, Sevagram

- Tata Medical Center (TMC), Kolkata

- Sir Ganga Ram Hospital (SGRH), New Delhi

- Apollo Hospitals, Chennai

- P.D. Hinduja National Hospital, Mumbai

- Armed Forces Medical College (AFMC), Pune

- King George’s Medical University (KGMU), Lucknow

- All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bhopal

- Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital (LTMMC & GH), Mumbai

- Assam Medical College & Hospital (AMCH), Assam

- Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences (NIMS), Hyderabad

- Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka (KMC)

- Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (IPGME & R), Kolkata

- Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS), Srinagar

- All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Jodhpur

The NCs and RCs follow standard operating procedures (SOPs) of Bacteriology and Mycology formulated by ICMR to collect resistance data. ICMR has developed a real-time online AMR data entry system and has AMR data analysis capacity. It is a user-friendly web-based solution for the collection, storage, and analysis of surveillance data. The analysis of the data from the surveillance network provides information required for targeted antibiotic policy and

implementation of antibiotic stewardship in a tertiary care medical facility.

AMR ICMR data for the year 2019 is available from the link: Visit Webpage

To know more about the regional centres and the nodal centres: Visit Webpage

Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) Surveillance in India

HAIs have tremendous implications in terms of associated mortality, morbidity, adverse patient outcomes, increased cost of treatment, and social impact. Apart from the escalating rates of HAIs, Multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms now increasingly cause these infections. The problem is further compounded by the severe paucity of new antimicrobials, making treatment extremely difficult. An important initiating point to curtail HAIs and AMR is through capacity building to ensure that systems, policies and procedures are in place to rapidly and accurately detect and monitor AMR and HAIs. The All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi is collaborating with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) to leverage the existing capacities for microbiology and robust academic capabilities of the ICMR-AMRSN to implement a step-wise, scalable process for quantifying, strengthening, and expanding the ability of the healthcare systems in India

to generate, apply and report accurate data of Healthcare-Associated Infections and AMR. This work, being conducted under the broader umbrella of Global Health Security, includes more than 25 hospitals, representing almost all regions and states of India. This project will strengthen the national capacity for surveillance of HAIs, using the modules developed at AIIMS, based on CDC’s NHSN guidelines. This will serve the need for reliable AMR data to support successful patient care, and public health needs to measure, track and report the magnitude and types of AMR and HAI threats affecting India, in accordance with stated GHSA goals. In addition, the clinical facility component of the proposal will assess and strengthen both clinical antimicrobial use practices and infection control capacities for the containment of AMR pathogens. For further information, Click here

Challenges in surveillance in India

Creating a sustainable AMR surveillance system is a challenge. This was identified by the GARP India working group. The challenges pointed out were securing cooperation from the various stakeholders across multiple sectors, establishing mechanisms for inter-state and cross-border coordination, and financial sustainability.

NARS-Net focuses on facility-based surveillance, especially from tertiary care centres. The network contains a large number of public sector hospitals and a limited number of private sector hospitals. This doesn’t provide a complete picture. There are high chances of underreporting of community-acquired resistant infections. Considering the national AMR Laboratory network in animal health and food safety sectors, India reports that laboratories perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for their purposes are not included in the national AMR surveillance system.

NARS-Net focuses on facility-based surveillance, especially from tertiary care centres. The network contains a large number of public sector hospitals and a limited number of private sector hospitals. This doesn’t provide a complete picture. There are high chances of underreporting of community-acquired resistant infections. Considering the national AMR Laboratory network in animal health and food safety sectors, India reports that laboratories perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for their purposes are not included in the national AMR surveillance system.

No standardized national AST guidelines are currently in place. The diagnostic techniques used and the data management procedures are not clearly described in the self-assessment survey 2019-2020. Surveillance in India doesn’t cover the antibiotic consumption data. Such a surveillance system is vital to track antibiotic consumption and to predict AMR emergencies, especially today as India is the largest consumer of antibiotics in the world. As per the AMR self-assessment survey response 2019-2020, while India has designed a monitoring plan in the case of the human health sector, there is no national plan or system for monitoring sales/use of antimicrobials in animals. The situation is similar in the plant sector where there are data on antimicrobial pesticides used in plants. Surveillance of AMR in animals and food is very limited in India. Though many small-scale studies were conducted across the country confirming the high burden of AMR, India still lacks national-level data on one health. Under the national surveillance system for AMR in animals, priority bacterial species have been identified. But AMR surveillance is not routinely carried out in animal (terrestrial and/or aquatic) isolates linked to animal disease, zoonotic pathogenic bacteria, commensal isolates and specific resistance phenotypes such as ESBL producing indicator E.coli obtained from healthy animals in key food-producing species. Without adequate data on antibiotic consumption and AMR across various sectors (humans, animals, plants, food production, food safety), it would be difficult for India to amend the national strategy or to inform decision-making.

For more information, Click here

NARS-Net focuses on facility-based surveillance, especially from tertiary care centres. The network contains a large number of public sector hospitals and a limited number of private sector hospitals. This doesn’t provide a complete picture. There are high chances of underreporting of community-acquired resistant infections. Considering the national AMR Laboratory network in animal health and food safety sectors, India reports that laboratories perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for their purposes are not included in the national AMR surveillance system.

NARS-Net focuses on facility-based surveillance, especially from tertiary care centres. The network contains a large number of public sector hospitals and a limited number of private sector hospitals. This doesn’t provide a complete picture. There are high chances of underreporting of community-acquired resistant infections. Considering the national AMR Laboratory network in animal health and food safety sectors, India reports that laboratories perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for their purposes are not included in the national AMR surveillance system.